“What do you hope will change as a result of this?” It was a question that had so many obvious answers.

But the Muslim worshipper looked at me emphatically, frustration in his eyes and in his voice.

“We want people to understand us better. We’re sick of being tarred with the same brush. Right now we are not blaming an entire race. We are not blaming an entire faith. We blame one person. The person who fired the gun.”

He had flown in from Auckland for the reopening of the Al Noor Mosque where 42 innocent people were shot dead a week earlier.

The place smelt of fresh paint. The bullet holes had been plastered over. The carpet ripped up. The blood washed away. Left behind was an eerie vacant building, a void filled with grief.

I’m the first to admit I knew very little about the Islamic faith before jumping on a plane to Christchurch to cover the worst mass shooting in New Zealand’s history.

But I’ve returned home in awe of the people, their principles, their approach to life and their unfathomable ability to forgive.

At the National Remembrance Service last Friday where the names of the 50 lives lost were read out, the crowd of 20,000 was told “when someone shows you hate, respond with love”.

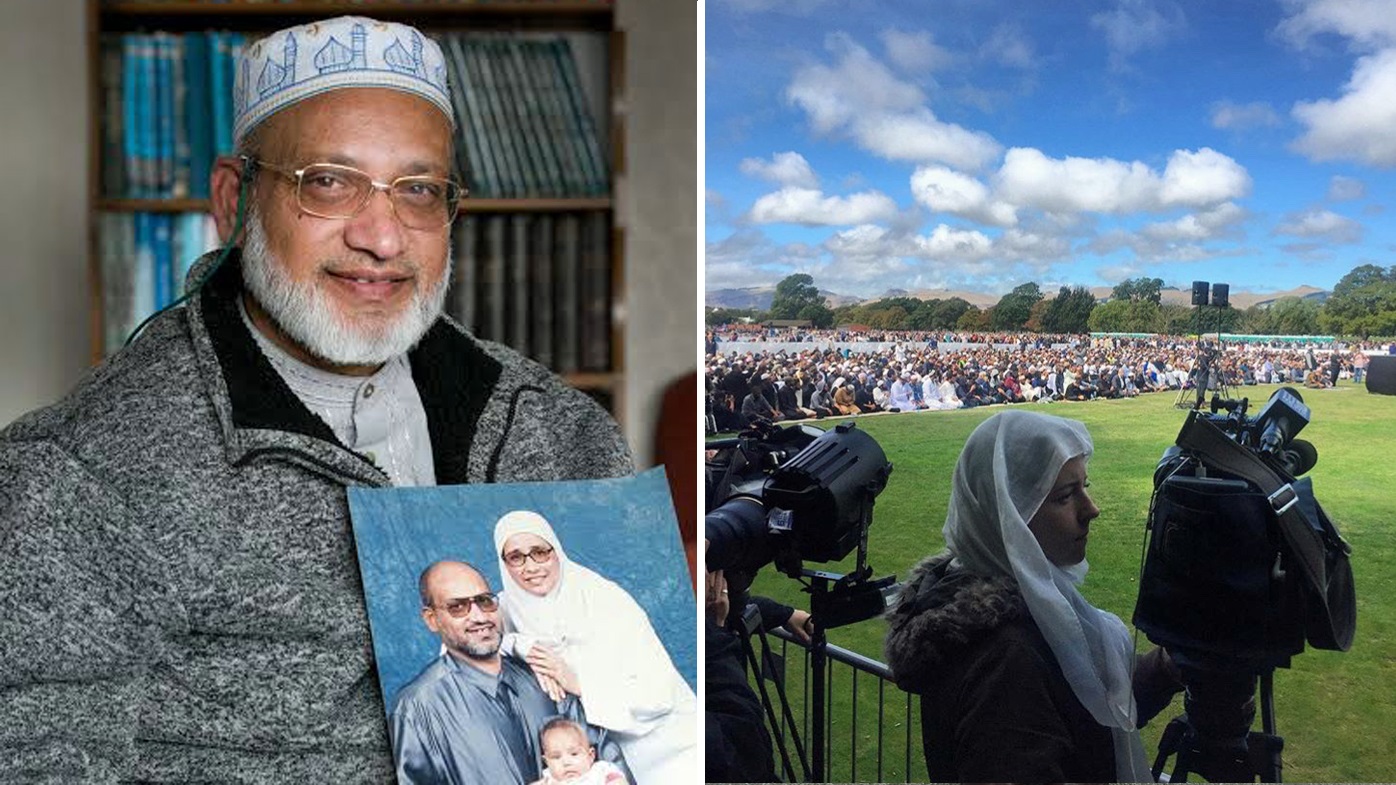

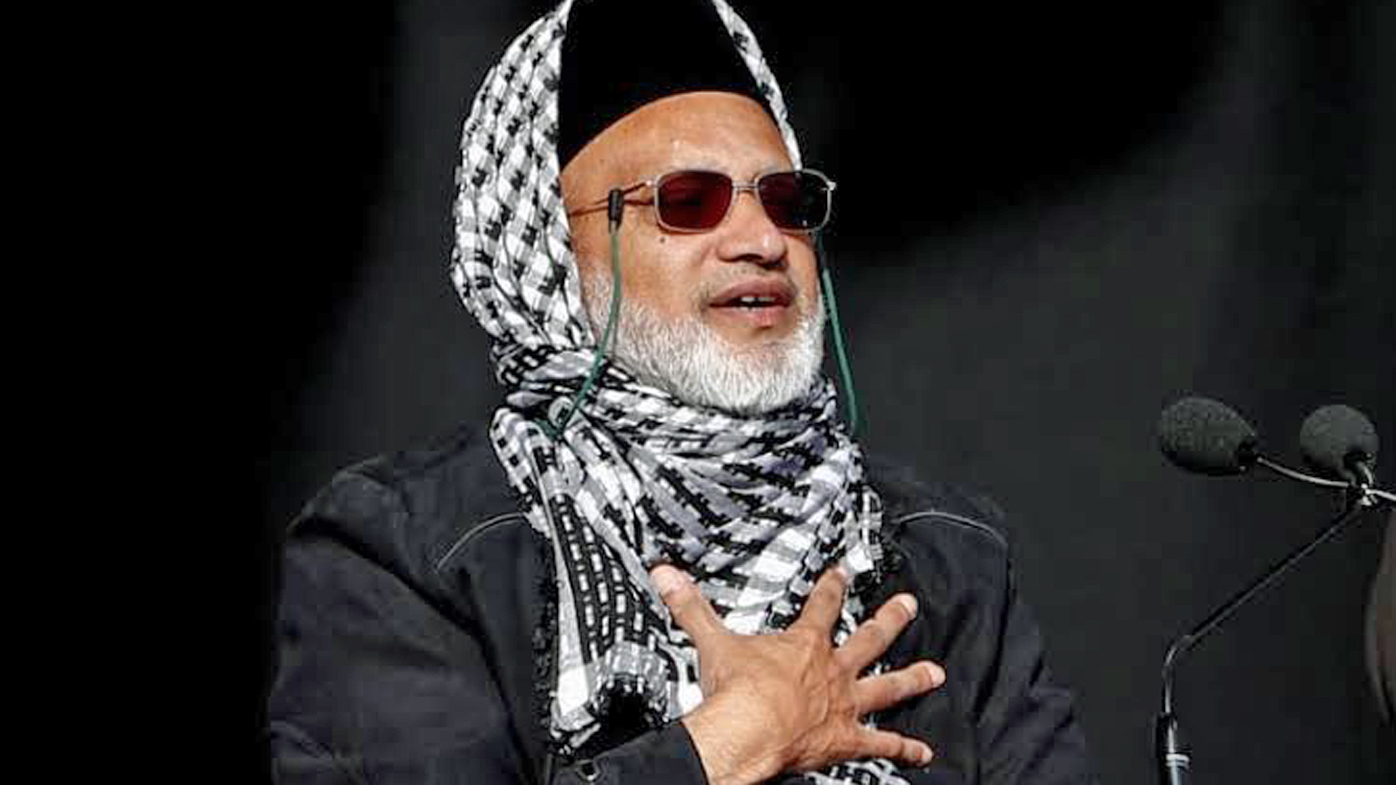

No one has put that into practice more courageously than Farid Ahmed whose beloved wife was shot dead as she tried to wheel him to safety. Speaking from his wheelchair on stage he explained why he had chosen to forgive the gunman.

"I don't want to have a heart that is boiling like a volcano. A volcano has anger, fury, rage; it doesn't have peace, it has hatred. It burns itself within and it burns the surroundings,” he said.

He went on to say he loves the mass murderer as a brother.

“I don’t agree with what he has done. I don’t support what he has done. Probably he has gone through some suffering in his life. Some traumatic thing happened to him and he couldn’t process it. I do not hate him. I cannot hate him. I cannot hate anyone.”

It’s extraordinary to think a man whose wife was so callously taken from him, could have the compassion to forgive her killer. I’ll be honest, I don’t think I could do the same.

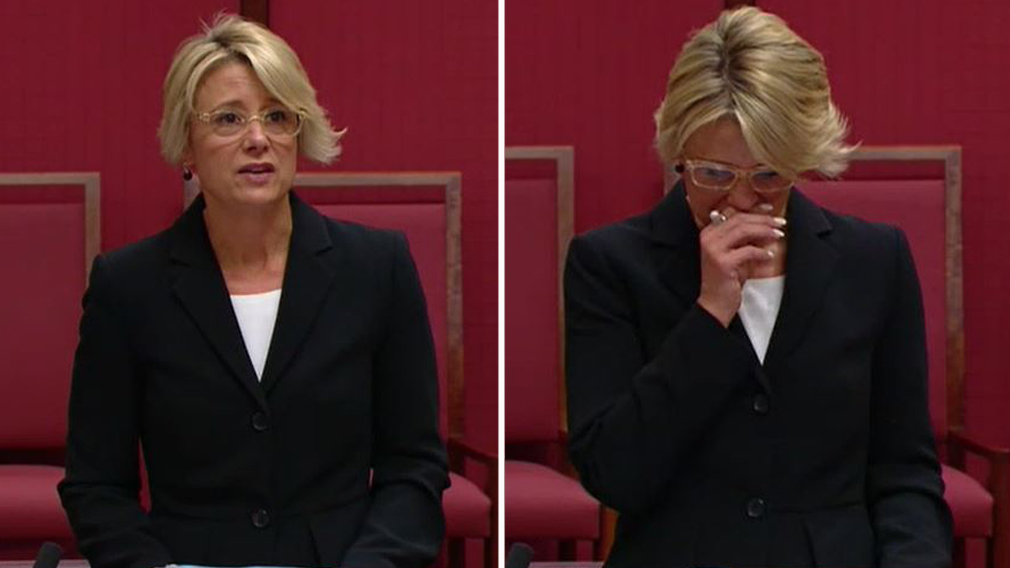

When covering a story like this, you carry a heaviness with you. There were times before a live cross or after when I broke down in tears.

Like the day the youngest victim 3-year-old Mucad Ibrahim was buried. He had been at the Al Noor Mosque with his dad when the gunman, high on hate, blasted through the front doors and opened fire.

Mucad thought it was a game and ran towards him. In the chaos that followed his tiny body was carried from the mosque by a stranger. It was days before his family learnt his tragic fate.

On another day I was outside the cemetery as the mass burials got underway. Waiting to go live into the Sydney news, I was rehearsing what I was going to say when I noticed a group of men in their twenties huddled outside the cemetery entrance.

One looked up at me apologetically. “Sorry, I’m so sorry,” he said. “I’ve just told my friends to be quiet because you’re about to go on TV.”

It broke my heart to think he was about to bury his loved one but was worried about interrupting me. “Please don’t apologise,” I said, thinking ‘I’m the one who is sorry. Sorry this happened to you’.

Muslims believe people killed in worship, go to paradise. In a small way this is helping their grief.

But the rest of the world can help too. By remembering regardless of how we look, how we dress, our faith, language or culture we are all one human family.

And it’s always easier to love than it is to hate.